Origins

Molecular clock analyses points to SARS-CoV2 establishing human-to-human transmission as far back as mid-October to mid-November of 2019 in Hubei Province, China, with “a likely short interval before epidemic transmission was initiated”.1 A paper by Pekar et al. in Science, used ‘coalescent framework to combine retrospective molecular clock inference’ to determine how long the virus was circulating before the time of the most recent common ancestor of sequenced genomes. The first described cluster was associated with the Huanan Seafood Market in December 2019. However, the market cluster is unlikely to have denoted the beginning of the pandemic, as early COVID-19 cases from the beginning of December lacked connections to the market. The earliest case was retrospectively diagnosed to the 1st of December.2 The paper gives an important insight into how early we should be looking at when transmission was established.

Notably, however, newspaper reports document retrospective COVID-19 diagnoses recorded by the Chinese government going back to 17 November 2019 in Hubei province (10). These reports detail daily retrospective COVID-19 diagnoses through the end of November, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 was actively circulating for at least a month before it was discovered.

Molecular clock phylogenetic analyses have inferred the time of the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of all sequenced SARS-CoV-2 genomes to be in late November or early December 2019, with uncertainty estimates typically dating to October 2019 (7, 11, 12).

What happened in Wuhan in the middle of October of 2019?

The Wuhan Military Games were held in Wuhan on the 18th of October, 2019. Many military athletes competed from all around the world. The Wuhan Military World Games was home to 9,000 international athletes from more than 100 countries.3 Nearly 300 members from the US military, Department of Defense, and support personnel attended the Military Games in Wuhan. When the games ended American athletes returned to at least 219 bases in 25 US states, without ever being screened for possible COVID-19 infection.4 However, 6 of the 138 soldiers who traveled to Wuhan in October from the Spanish delegation did test positive for COVID-19 antibodies.5 According to the Pentagon there was no reason to screen athletes or subsequently. “A spokesperson issued a terse email response to the question, saying there was no screening because the event — held from October 18 to 27, 2019— ‘was prior to the reported outbreak’”. 6 The spokesperson cited December 31, 2019, as the critical outbreak day where no testing was deemed necessary for any possible exposure prior to February 1st, 2020. Contrary to the Pentagon’s insistence, there are sources and materials that prove there is a strong correlation between COVID-19 cases reported at the US military facilities that are home bases of members of the US team that went to Wuhan as well as the prevalence of COVID-19 cases in the country to which international athletes returned.7 The Pentagon restricted the release of information about cases before the 31st of March at military installations for ‘security reasons’; infections occurred at 63 facilities where team members returned after the Wuhan games. Josh Rogin in The Washington Post reports, that during the two-week event many of the international athletes noticed that something was amiss in the city. Some described it as a “ghost town”.

An anonymous athlete came forward to this publication and described the town as a “desert” and that when returning from Wuhan to North America, he wasn’t tested and ended up infecting his family with a respiratory illness. There were French, Italian, and Iranian athletes returning from the Games who also reported suffering from COVID-19 like symptoms. The reluctance to test athletes wasn’t unique to the U.S.

When asked why the athletes and support staff who had been in China were not screened as a precaution once the COVID-19 threat was known in January, Defense Secretary Mark Esper said at the end of an April 14 press conference: “I am not aware of what you are talking about.”

The question and response were not included in the Pentagon’s official written transcript of the briefing, as is the normal procedure. The official video of the briefing goes silent when the question is asked and Esper can be seen—but not heard—reacting to the question.

Here is Mark Esper giving that answer at 50:11

April 14th, 2020

Reporter: Any special screening for military team that went to Wuhan to athlets [mispronunciation] … athletic team?

Mark T. Esper: I’m — I’m not aware of what you’re talking about.

General Mark Milley: Yeah I’m not —

Reporter: In November they had a team in Wuhan.

[END]

Databases

As most readers should be aware, in September 2019, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (the lab implicated in a lab leak origins theory), deleted a public database containing information on at least 16,000 virus samples.8 Peter Daszak, of EcoHealth Alliance, asked Dr Shi Zhengli why it was deleted, Zhengli responded that they had been forced to take it down after about 3000 hacking attempts. In a virtual panel discussion in early March 2021, Daszak said it was “absolutely reasonable” that the database was taken offline and revealed the team did not request to see it because he personally vouched for the lab based on his group’s previous collaboration, stating that it was not relevant to the origins of the pandemic, Australian Broadcast Channel reports.9

“A lot of this work is work that has been conducted with EcoHealth Alliance. I’m also part of those data and we do basically know what’s in those databases … I got to talk with both sides about the work we’ve done with Wuhan Institute of Virology and explained what’s there.”

Dr Daszak said there was “no evidence of viruses closer to SARS-CoV-2 than RaTG13 in those databases”, referring to a bat coronavirus similar to the virus that causes COVID-19.

There was also a case of genetic sequences being deleted on an NIH database. Wuhan University asked for sequences to be removed from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), a repository for raw sequencing data maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), part of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).10 The NIH obliged and removed that data at the request of the researchers, who said that they planned to submit them to another database. However, partial sequences have been uncovered since this deletion.

A biologist in the United States recovered partial SARS-CoV2 genome sequences from the beginnings of the pandemic’s probable epicentre in Wuhan, China.11 These sequences that were found in a research paper, from May 2020, have shed some light on how closely sequences from Wuhan relate to the original bat ancestor. The earliest sequences from Wuhan that were collected at the seafood-market are more distantly related to SARS-CoV2’s closest relatives in bats than are later sequences, including ones collected in the United States.12 Bloom’s paper (published August 16 2021) includes the newly recovered sequences that have helped to infer a very interesting finding. Most known human SARS-CoV2 sequences are consistent with an expansion from one progenitor (ancestor) sequence. However, attempts to infer the ancestor sequence have been met with a perplexing fact, the earliest Wuhan sequences are — the sequences that are least similar to SARS-CoV2’s ancestral relatives.

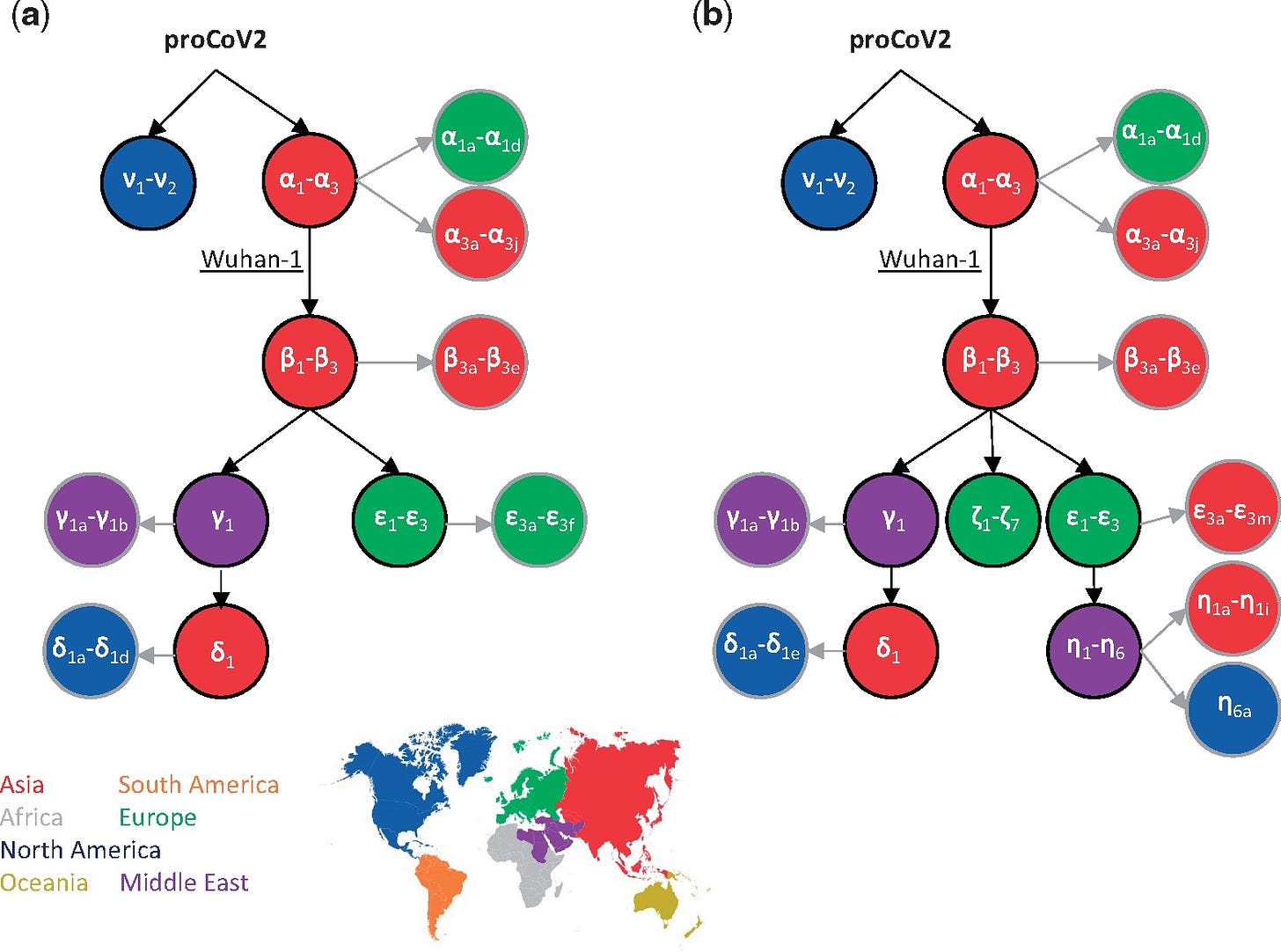

A paper from Kumar et al. (published 4 May 2021), expands on the phylogenetic analyses of others and builds on more traditional estimations, that use rooted phylogeny, and instead uses a mutational order approach (MOA). This approach directly reconstructs the ancestral sequence and mutational history of CoV-2 genomes. This paper rooted the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all the genomes analysed, which gave rise to two early lineages α and ν. The MRCA genome was the progenitor of all SARS-CoV2 infections globally, dubbed proCoV2 in this paper. When compared with Wuhan-1 genomes and other early samples, the Wuhan-1 strain evolved by 3 successive mutations. 896 intermediate genomes contain one or two α variants in the data set. Three closely related nonhuman coronavirus genomes all have the same base at these positions as does the proCoV2 genome, this suggests that the ancestral genome did not contain α variants.13

What does this mean? that the coronaviruses lacking α variants were the ancestors of Wuhan-1 therefore we conclude that Wuhan-1 was not the direct ancestor of all the early coronavirus infections globally. Put simply Wuhan Seafood Market was not the source of the pandemic. A comparison of proCoV2 revealed three matches in China and three in United States (Washington), sequenced in January 2020. The ν mutant of proCoV2 was first sampled 59 days after Wuhan-1 strain which means the progenitor coronavirus spread and mutated in the human populations for months after the first reported COVID-19 cases.14 Multiple matches were found in other continents detected as late as April 2020 in Europe. These patterns suggest that proCoV2 already possessed the repertoire of protein sequences needed to “infect, spread, and persist” in the global human population. Where was this early spread happening and can we detect it?

The progenitor of all genomes is three bases different from the Wuhan-1 genome (Dec) which extends the ancestry before late November that has been suggested by Pekar et al. above. Pekar’s root position was the same as Wuhan-1, and Pekar’s data did not include 1,000 genomes that comprise the early diverging ν lineage sampled in North America which was descended from an earlier ancestor that also gave rise to the genome (α lineage) at the root of Pekar et al. paper. This is troublesome because what this obfuscates is that there was earlier transmission before the date Pekar established.

Our timings of MRCA (tMRCA) is 1 month older than the date for the MRCA of genomes presented by Pekar et al. (2021) because their analysis is restricted to the ancestry of the coronaviruses sampled from China only, which resulted in the exclusion of the ν lineage from their analysis. The potential for not sampling such lineages is well appreciated in Pekar et al. (2021). This exclusion and the use of sampling times in strict clock phylogenetic analyses would naturally lead to analyses leaning closer to the earliest sampling times of SARS-CoV-2 (December 2019). Anyway, if we assume that proCoV2 was the index case, then the date of zoonosis (tIndex) would be late October to mid-November 2019. This range overlaps with Pekar et al.’s (2021) index date falling between mid-October and mid-November 2019. However, it likely that the actual tIndex is much earlier than tMRCA because proCoV2 likely increased in frequency over time before reaching a human host, and it is possible that one of its immediate ancestor first infected a human. Based on an approximately 1-month difference between MRCA and Index dates in Pekar et al. (2021), it is tempting to speculate that tIndex could have been as early as September 2019 for our SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny. This speculation requires more extensive analysis and experimental confirmation in the future.

Fort Detrick

From September 2019, the Pentagon withheld $104 million, from research labs at Fort Detrick and Aberdeen, and it had members of Congress and Senate wondering why. In a letter, dated February 5th, 2020, addressed to Mark T. Esper, Secretary of the U.S. Department of Defense, members wondered:

As our nation prepares to confront the coronavirus global health emergency, we write to express our concern regarding the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD(A&S)) withholding $104 million in payments to the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick and the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD) at Aberdeen Proving Ground.

As you know, USAMRIID is the Department’s lead laboratory for medical biological defense research. Their research helps to protect the American warfighter from biological threats and investigate disease outbreaks and threats to public health. Research conducted at USAMRIID leads to therapeutics, vaccines, diagnostics, and information that benefit military personnel and civilians. USAMRICD is the nation’s leading science and technology laboratory in the area of medical chemical countermeasures research and development.

Given the critical contributions of USAMRIID and USAMRICD to our national security, including their role in responding to the coronavirus outbreak, we were alarmed to learn that the OUSD(A&S) has withheld payment for laboratory research since September 2019. 15

Members continue the letter expressing their concern that the labs have been withheld payment, for research, since September 2019 and the Defense Department’s efforts to make drastic programmatic changes without consulting Congress.

It is unusual that key laboratories involved in biodefense research and vaccine development would have their funds restricted in such key moments of what would later be the COVID-19 pandemic. USAMRIID is the Defense Department’s research facility on biological defense, where they study highly lethal pathogens such as Anthrax, Coronaviruses, Plague, Ebola, and Marburg hemorrhagic fevers. USAMRIID explains its role on its website:

We continue to develop new and improved vaccines, working with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to move medical products forward using the "animal rule."

Under this rule, specifically designed for biodefense vaccines and drugs, products can be considered for FDA licensure using data from animal studies in cases where human clinical trials cannot be conducted. USAMRIID continues to be a leader in developing animal models for a variety of biological threat agents and validating that these models adequately reproduce critical aspects of human disease.

USAMRIID's therapeutics program is focused on broad-spectrum antiviral and antimicrobial drugs against multiple biological agents. We also continue to discover and develop therapeutic interventions for diseases caused by toxins such as botulinum neurotoxin.USAMRIID develops new, faster diagnostic assays for medical identification to protect the warfighter against biological threats. We also evaluate and develop diagnostic instruments and technologies for use in forward field medical laboratories and with the Joint Biological Agent Identification and Detection System (JBAIDS), the diagnostics platform used across the DoD.

Through a partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the DoD Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System, USAMRIID transitioned the CDC diagnostic assays for avian influenza and swine flu to the JBAIDS platform, enabling all military organizations with the JBAIDS platform to use the CDC assays for rapid detection of these viruses.

In addition, we performed the necessary studies leading to an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the FDA for use of these assays on the JBAIDS platform. That work has led us to preposition a number of additional diagnostic assay data packages for rapid EUAs in the event of an emerging biological threat.

Why were these labs underfunded at such a crucial time?

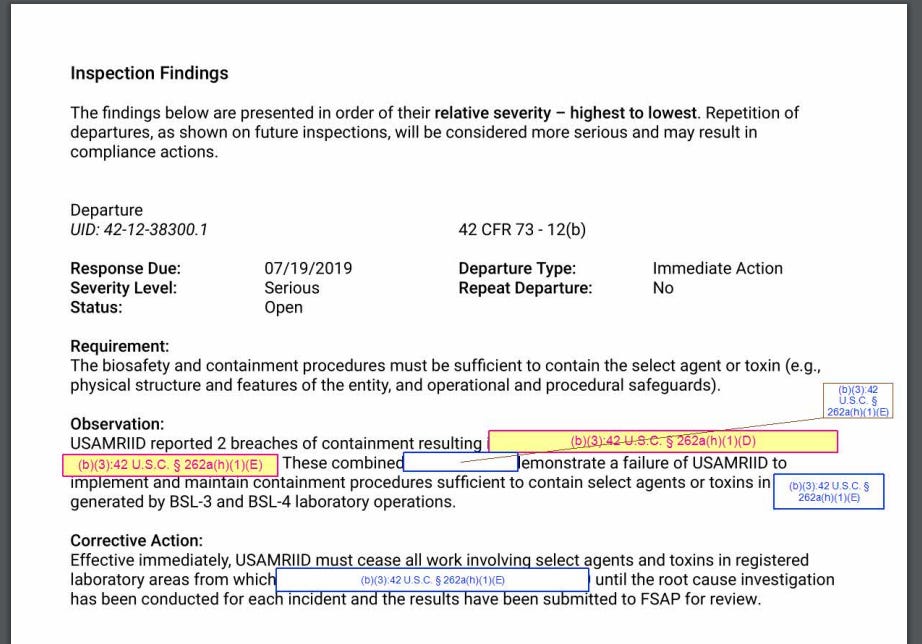

On the 2nd of August 2019, The Frederick News-Post reported that Fort Detrick was asked to close all research into some of the deadliest viruses and pathogens over fears that contaminated waste could leak out of the facility.16 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent a cease and desist order in July.

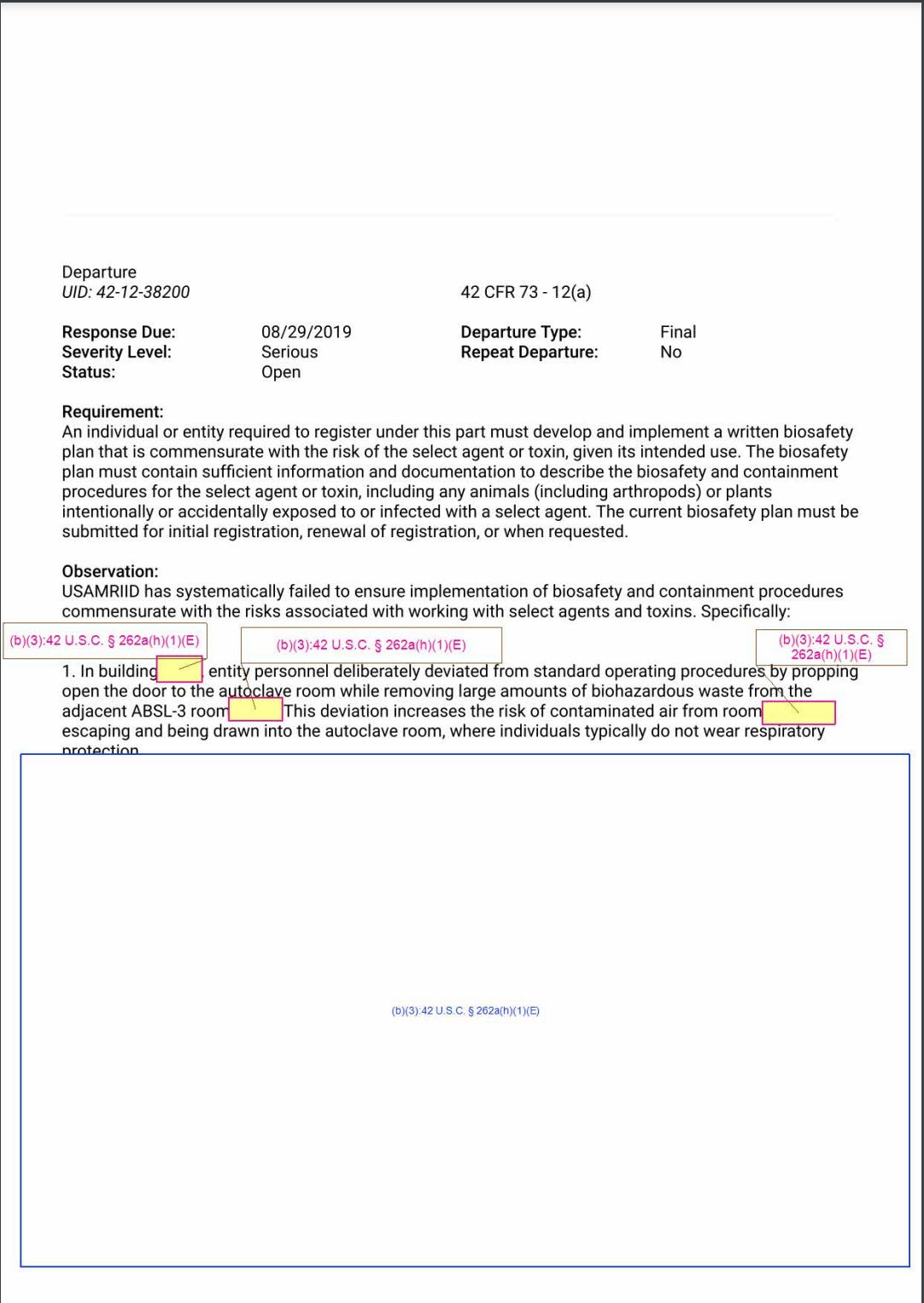

Here are the concerns

All research that involved the handling of disease-causing material was put on hold indefinitely as the CDC found the organisation failed to meet biosafety standards. The CDC inspected the institute in June 2019 and inspectors found several areas of concern in standard operating procedures. These procedures are in place in order to protect workers in biosafety level 3 and 4 laboratories. There were multiple causes that affected the suspension — failure to follow local procedures and a lack of periodic recertification training for workers in the biocontainment labs. The wastewater decontamination system also failed to meet standards set by the Federal Select Agent Program. According to the Code of Federal Regulations, which also lists training, records, and biosafety plans, Federal Select Agents Program registration can be suspended to protect public health and safety. It is not clear if this is why the USAMRIID registration was suspended, Frederick News-Post writes. USAMRIID spokeswoman Caree Vander Linden writes:

While the Institute’s research mission is critical, the safety of the workforce and community is paramount. USAMRIID is taking the opportunity to correct deficiencies, build upon strengths, and create a stronger and safer foundation for the future.

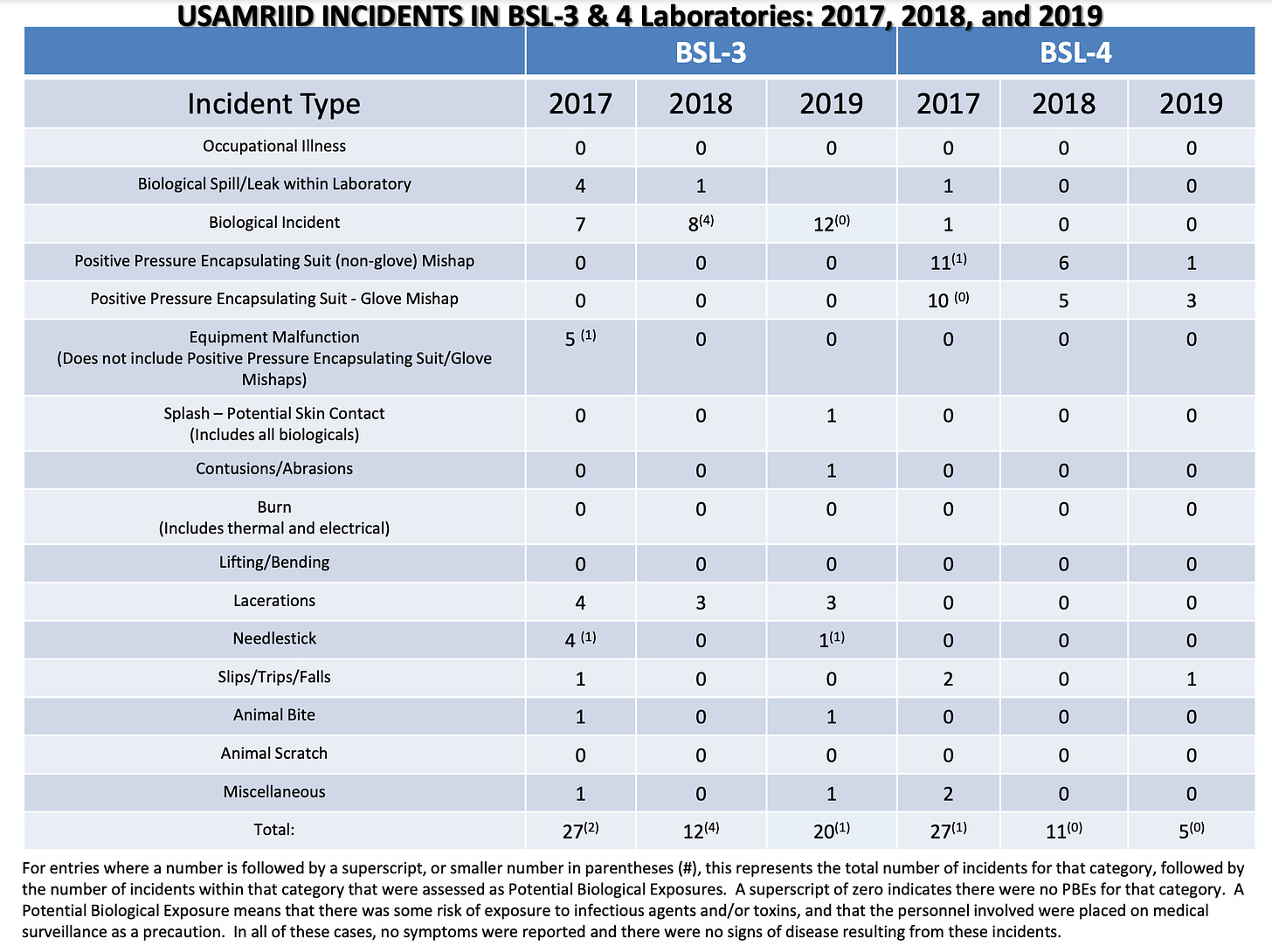

This hasn’t been the first time that a biosafety incident has happened at USAMRIID. Here is a chart, provided by USAMRIID, of all the incidents that have happened at Fort Detrick since 2017 in the BSL-3 and 4 labs.17 Strangely the biosafety concerns that forced the CDC to completely close down the lab aren’t mentioned in their chart for 2019.

Respiratory Outbreak

Springfield, VA

July 11th, 2019

ABC News reported on the 11th of July that a “respiratory outbreak” has killed two people — and 18 others were hospitalised — at a Virginia retirement community.18 The Fairfax County Department of Health said that 54 individuals had become ill with “respiratory symptoms ranging from upper respiratory symptoms (cough) to pneumonia” in the last 11 days (as of July 11th) at Greenspring Retirement Community in Springfield. In a letter that was sent to residents, Greenspring described the symptoms of the virus outbreak as “fever, cough, body aches, wheezing, hoarseness and general weakness.” Benjamin Schwartz the health department director told ABC News that the outbreak had been reported at the assisted-living sections and said the first outbreak began with a case on June 30th. The cause of the outbreak has not been identified according to Greenspring. The assisted-living and skilled-nursing facility in Greenspring is home to 263 residents. Schwartz said that the two patients who died in the outbreak had been hospitalized with pneumonia but were “older individuals with complex medical problems.”

Seeing a respiratory outbreak in a long-term care facility is not odd. One thing that’s different about this outbreak is just that it’s occurring in the summer (emphasis added) when, usually, we don’t have a lot of respiratory disease.

Burke, Virginia

July 17th, 2019

A second Fairfax County retirement community is battling an unusual summertime outbreak of a mysterious respiratory illness, reports WJLA ABC 7 News.19 The Fairfax County Health Department in a press conference included information regarding Greenspring Retirement Community and another long-term care facility, Heatherwood, in Burke. Heatherwood as of July 17th experienced 25 cases where two have developed pneumonia but at the time no one died. The Health Department claimed that it was in no way connected to the outbreak in Greenspring where 3 have died. In addition, 19 employees have also reported respiratory symptoms.20

CDC received 17 specimens from ill Greenspring residents but did not identify a cause of the outbreak. Samples from Heatherwood have also been sent to the CDC.

August 2nd, 2019

Virginia health officials have found that there was a rise of reported outbreaks of respiratory illnesses in the summer of 2019, such as the one that contributed to the deaths of three people and sickened dozens more at an assisted-living facility in Northern Virginia. The rise of outbreaks has increased by roughly half. 21 Jonathan Falk, epidemiology program manager at the Virginia Department of Health, said the number of such outbreaks in 2019 rose to 19, compared with the dozen or so that normally occur outside the flu season. Several infections occurred in assisted-living facilities for older people such as the Greenspring Village in Springfield. Three people have died, 23 were hospitalised and dozens more fell ill during an outbreak of respiratory illnesses that struck Garden Ridge, the community’s assisted-living and skilled nursing unit between June 30th and July 15th. The infection also spread to Greenspring’s staff affecting 19 employees at the complex.

It’s not clear why the outbreak occurred in Greenspring or why there has been an increase in reported cases around Virginia, health officials said. Neither the District nor Maryland has detected anything similar, according to state health department officials in those jurisdictions.

The increase in respiratory infections in Virginia prompted M. Normal Oliver, the commonwealth’s health commissioner, to issue an advisory last month to clinicians alerting them to the rise in reported outbreaks.

We were well above a dozen outbreaks reported in our system, and that’s not even getting into the back-to-school season.

In the period since mid-May, when the flu season ends, and October, when the number of cases picks up again, Virginia’s reporting system has counted 19 outbreaks including 13 at long-term care facilities. That compares with 13 similar outbreaks of flu season in 2018 and 15 in the previous year, Falk said.

Virginia health officials noted that laboratory tests identified a variety of causes of the outbreaks, including pathogens for Legionnaire’s disease, flu, the common cold, and pertussis, or whooping cough. In some cases, no common agent has been identified. In an update on July 29th, the Fairfax County Health Department said testing conducted by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on samples from Greenspring identified the virus that causes the common cold. There has been an unusual number of illnesses reported there since July 15th, officials said.22

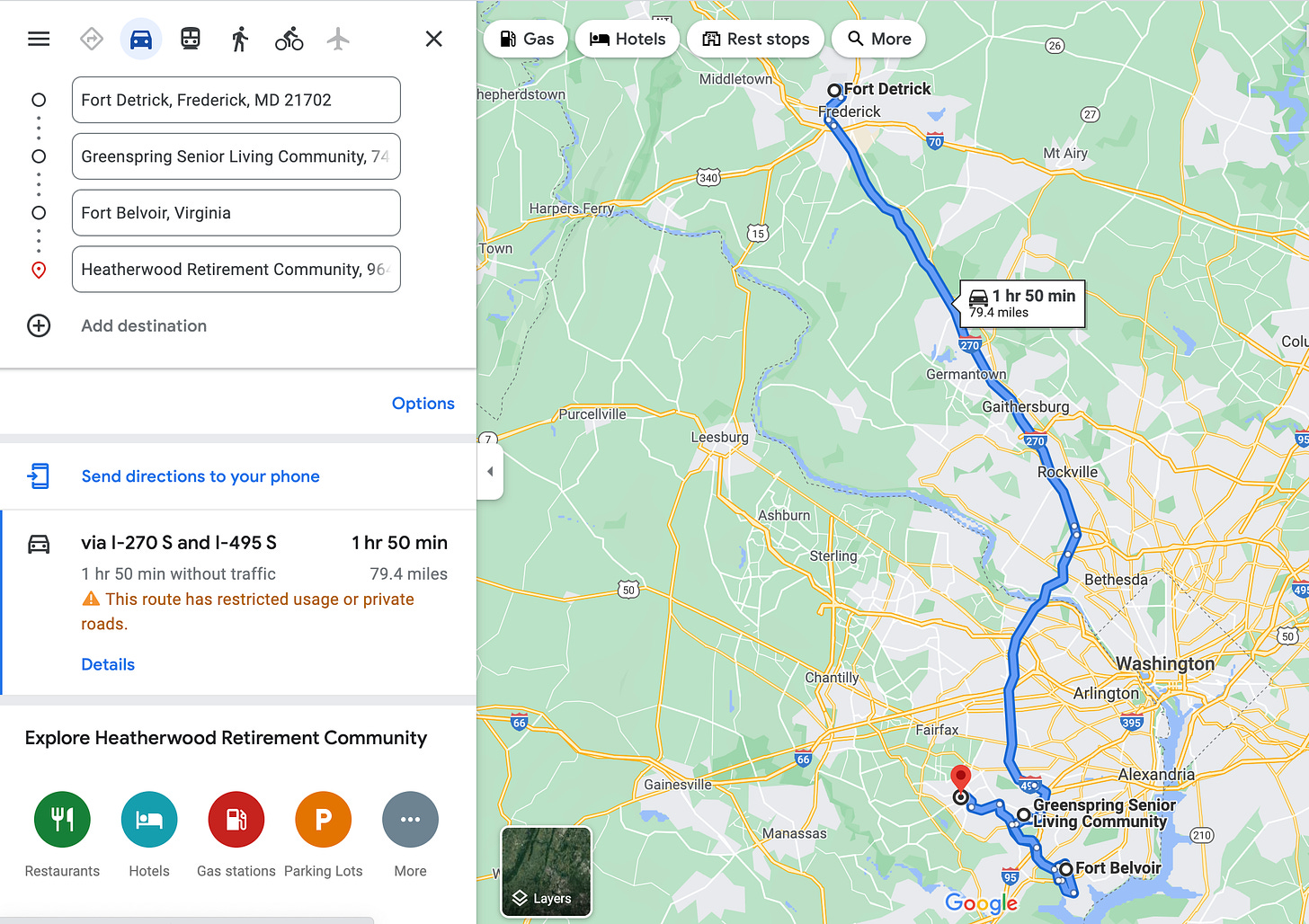

Fort Belvoir is a military, as well as a community, hospital situated near Washington in Fairfax County Virginia. It is home to more than 145 mission partners and it provides services to more than 216,050 military personell, civilians, retirees and families. Belvoir is the home of DTRA. It is a 45 min drive from Greenspring retirement community.

EVALI

“One Monday I just woke up and I was just feeling really sick and I just thought I was coming down with a cold or something.”

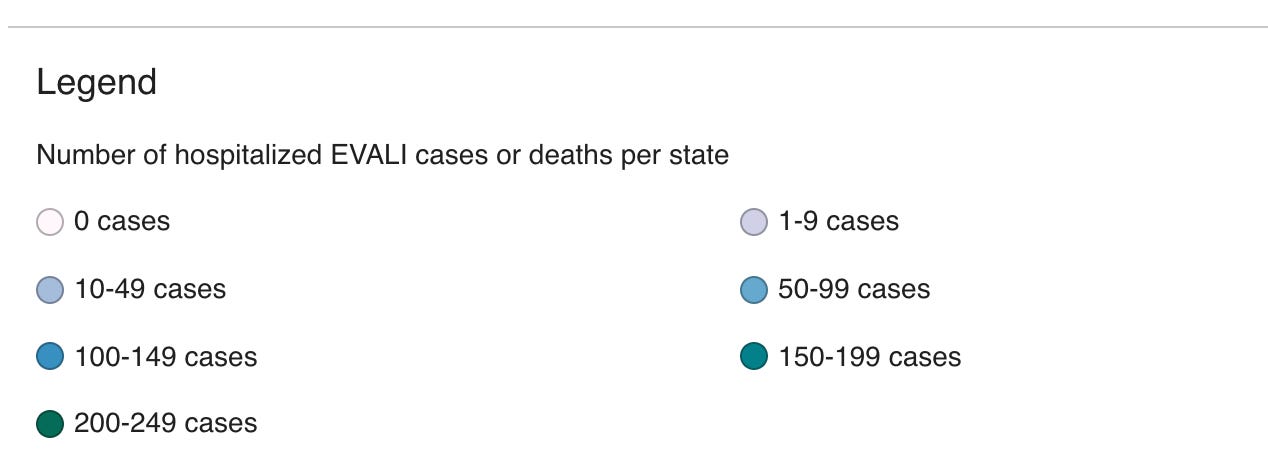

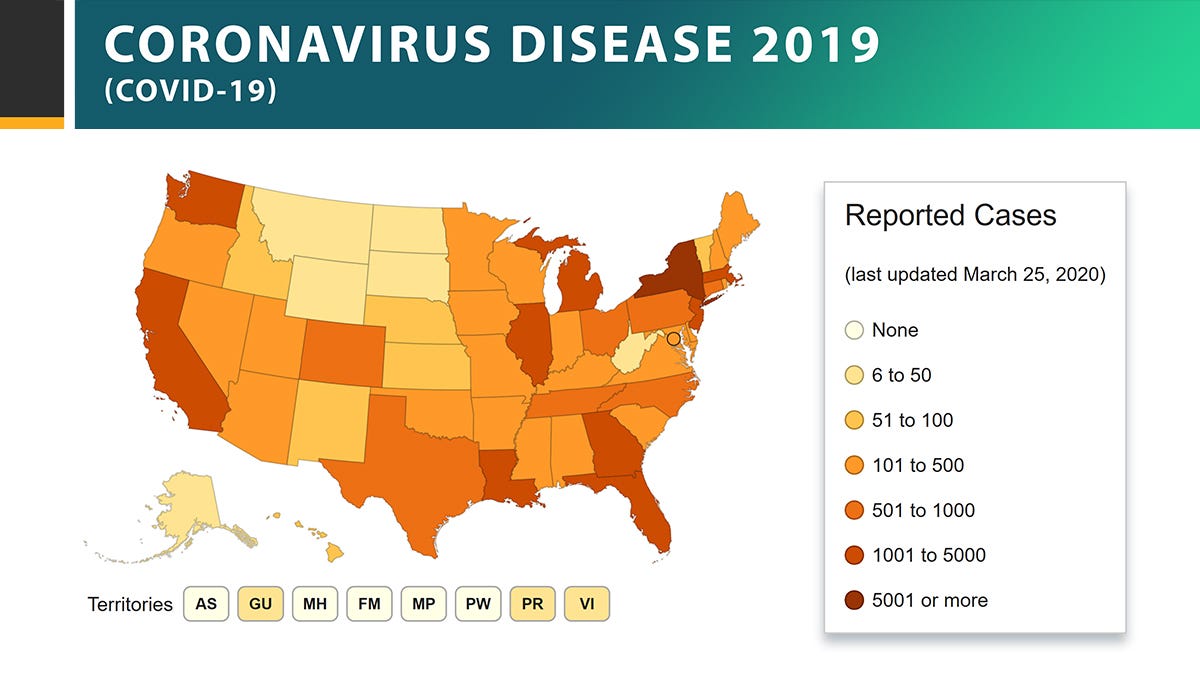

Nicotine vaping has become a popular alternative to tobacco smoking worldwide. In the U.S. 6.9 million adults vape nicotine — cannabis or THC oil vaping is also popular but not as common and its legal status depends on the state. In April 2019, a few reports emerged from the US of lung damage cases amongst people using e-cigarettes or vaporisers. The onset of symptoms was gradual with “breathing difficulty, shortness of breath and/or chest pain before hospitalisation”.23 By November, the number had reached 2290, including 47 deaths, across 49 states. The outbreak may have peaked with the number of cases falling.24

FDA and the CDC are charged with protecting the public’s health, they published a number of public alerts and advisories on the epidemic since the 17th of August 2019. These agencies initially provided different public advice on the outbreak.25 According to the FDA many cases were ‘associated with the vaping of THC products’ and some may be caused by vaping cannabis-based oils to which vitamin E has been added. It advised consumers to avoid vaping products that contain THC, not to buy ‘vaping products of any kind on the street’, and to refrain from using THC oil or modifying/adding any substances to products purchased in stores. However, no causal relationship was ever found and CDC doesn’t mention vitamin E acetate in its diagnostic rubric. In a paper looking at the pathology of EVALI using lung CT scans, the authors declare that EVALI has a nonspecific clinical presentation. Authors also observe whether Vitamin E has a causal role and can be used as a diagnosis of this unusual lung injury.

Recently, vitamin E acetate was isolated from 29 of 29 bronchoalveolar lavage specimens submitted to the CDC from patients with EVALI, but its role in the pathogenesis is still under investigation (51). This finding could be related to confirmation bias, wherein an inert substance (vitamin E) is blamed for being the causative agent, but is merely associated with another agent(s) that were not found at the initial toxicologic evaluation of the bronchoalveolar lavage material (eg, a so-called red herring).

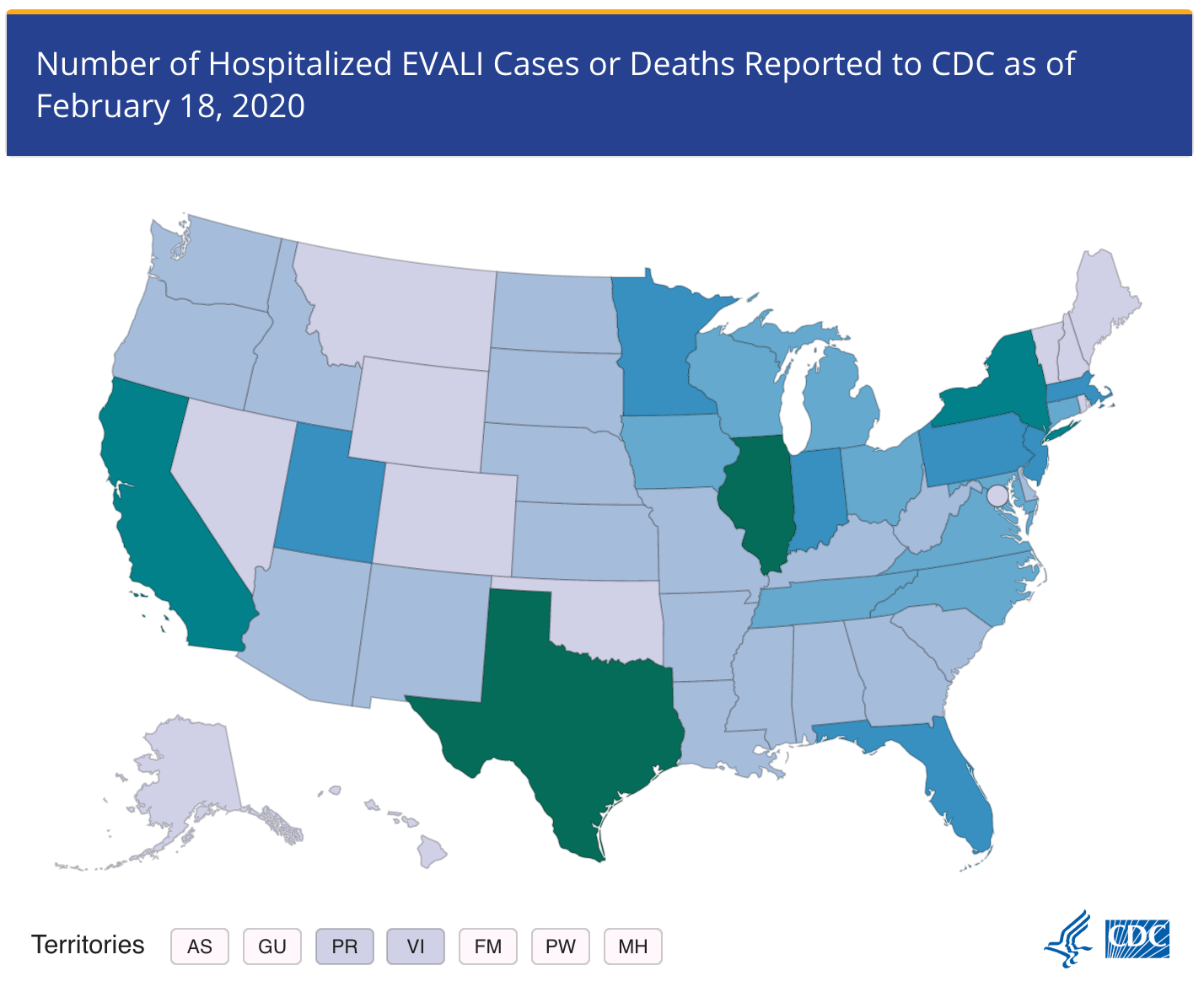

Here is a heat map image of EVALI occurrence across the US. Unusually correlating to the outbreak of the novel SARS-CoV2. Coincidentally the darker coloured states have higher populations as well as population densities.

Symptomatology of EVALI is difficult to pin down as it resembles other conditions such as infections. There is a strong overlap between EVALI and COVID-19.26 Aubree Butterfield was a patient at the University of Utah Health, she describes her symptoms of ‘EVALI’ in this video.

One Monday I just woke up and I was just feeling really sick and I just thought I was coming down with a cold or something.

Alexander Mitchell another patient at Utah Health described his difficulty with the condition:

I started getting chest pains, it was hard to breathe, I was coughing, we just figured it was some bug.

It was unusual that there were so many cases in the United States but not in other countries. Most of the cases in the US developed suddenly within a short period, in mostly young males. However older men (unlikely to use vaping products) were affected at a higher rate and were more likely to die from the complications. Most cases strangely developed in only one country. Over 40 million people have vaped nicotine in the UK, USA, and Europe and vaping has been around for nearly a decade without any similar clusters of serious acute cases of lung injury. If vaping nicotine were the cause of these lung injuries many more cases should have been reported in these countries soon after vaping products began to be used in the late 2000s. A preliminary report noted that ‘No previous case series … has described large clusters of temporally related pulmonary illnesses linked to the use of ecigarrete products'.27

Until recently data from Layden et al. only published the first series of 53 patients with EVALI in Wisconsin and Illinois. Only a few cases outside the US were recorded, in Canada and Japan. A paper submitted to the European Respiratory Journal (November 21, 2019), found a case of a 31-year-old woman who lived in Chicago (Illinois, USA) and arrived in Barcelona (Spain) on vacation on September 17, 2019 and suffered EVALI. This was the first case of EVALI in Europe. She attended the emergency room of Hospital Clinic in Barcelona after a 72-hour history of fever, myalgia, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue.

Cases started to pop up in Canada too. Where symptomatology wasn’t as severe but tracked with what was being reported out of the US. 28 VALI(EVALI) in Canada was found between September 2019 and December 2020. It was found at a much lower rate and as the authors of this paper speculate perhaps “through a different mechanism” than EVALI in the US. Unlike in the US, vitamin E was not identified in any of the products associated with VALI cases in Canada. The authors declare that no causal relationship can be assumed and no single agent is responsible for the lung injury. Interestingly, in March 2020, when COVID-19 became widespread in Canada VALI active surveillance was paused — paralleled by the US.

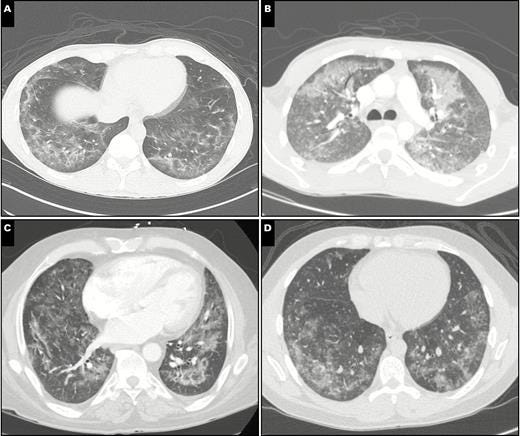

In this video Sanjay Mukhopadhyay MD, covering his article, focuses on the pathology of EVALI. EVALI has a significant overlap with COVID-19. Here are some of the comparisons that we can make. Here we can see the CT scans from patients that presented with EVALI. If there are no abnormalities the characteristic look of a healthy lung is black, but the 4 cases below have a similar bilateral (both lungs) pattern of ground-glass opacities (GGO).29 In the more dense areas of the lung we get what is called consolidation. These abnormalities also occur in COVID-19.30

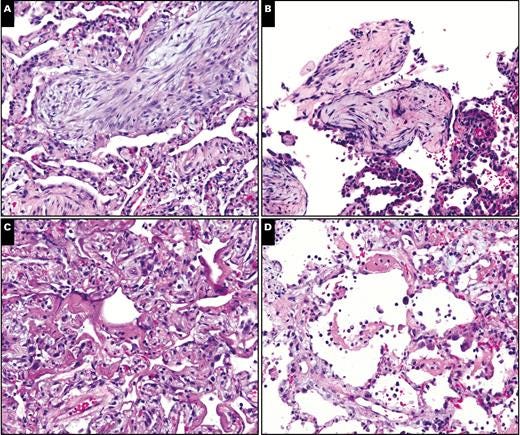

In the next image we see cross-sections of lung tissue. In image B we have what is called, Organising Pneumonia. COVID-19 also presents the same condition.31 In Image C, we have Diffuse Alveolar Damage (DAD) a severe lung injury that is normal in patients who end up going to ICU and put on a ventilator. COVID-19 is also characterised by the presence of Diffuse Alveolar Damage.32

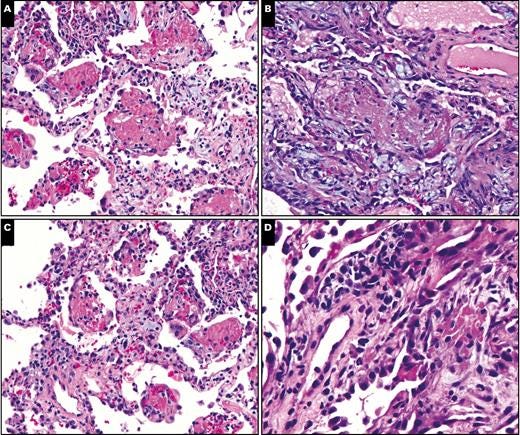

Fibrinous airspace exudates are present in Image B below in an EVALI case, also present within COVID-19 pathology.33 34

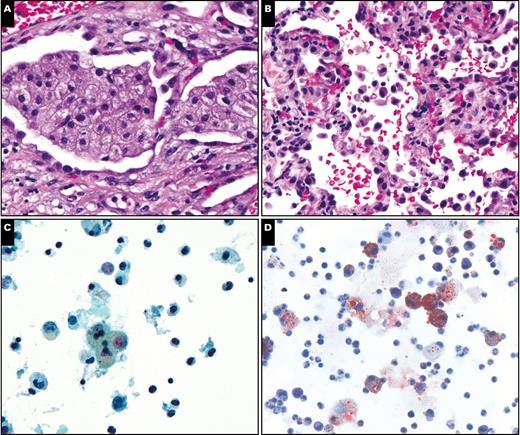

In Image B below, most importantly, EVALI presents a particular cell called a macrophage. Which is present in both EVALI and COVID-19. Another aspect that the author brings up is the lack of evidence for exogenous lipoid pneumonia which appears absent from the lung CT scans of EVALI patients as is claimed in the video from Utah Health.

In this paper Mukhopadhyay et al. describe:

One patient (61-year-old man, case 3) developed severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (emphasis added). His condition continued to deteriorate, with worsening hypoxia and fever, and his course was complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia on day 21 of admission. Despite receiving appropriate antibiotic therapy and mechanical ventilation, his condition worsened and he died on day 31 of admission.

COVID-19’s overlap with EVALI is interesting and gets discussed in this paper presenting 3 cases of EVALI. Several common symptoms run through each case with the authors concluding the difficulty in distinguishing between COVID and EVALI. Common symptoms of the lung injury include cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath, which occur in 95% of patients. Constitutional and gastrointestinal symptoms are also common, occurring in approximately 85% to 100% and 77% of patients, respectively. Progressive hypoxemic respiratory failure due to acute respiratory distress syndrome develops in approximately 22% of people, requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. There has been some success with using corticosteroids to treat EVALI. Interestingly, also used to treat COVID. All three cases in this study came back negative for SARS-CoV2 infection using nasopharyngeal swabs PCR test. The gold standard of SARS-CoV2 detection — still remains the nucleic acid amplification test — the sensitivity and specificity are high given ideal conditions however the authors do note a caveat.

… the test performance is dependent on both specimen quality and duration of illness at time of testing, with false-negative rates ranging from less than 5% to 40%, depending on the specimen source.

Whether three negative COVID cases is enough to categorically prove that EVALI and COVID-19 are different is up for debate. We would argue, given what we’ve seen and learned through molecular clock analyses, the start of the pandemic was certainly earlier, seeding around October/November 2019 in China. Yet the virus was well adapted to human lung tissue in China and hit the ground running? We hypothesise that EVALI is COVID and an earlier outbreak happened prior to Wuhan.

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

When they tested white-tailed deer in the US, they found SARS-COV-2 antibodies in 3 samples from January 2020 - ie predating the supposed US index case, which I read was a scientist or researcher returning from Wuhan via a somewhat circuitous route. This evidence of early wild deer infection only merits a casual mention in articles about these animals being a possible reservoir, and the risks that presents, eg NatGeo: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wild-us-deer-found-with-coronavirus-antibodies

What a fantastic deep dive, fab resource thanks! Because good stuff tends to vanish I have saved at Wayback and encourage you to make sure your other research and references are protected for posterity! :~)

https://web.archive.org/web/20220318011521/https://therequestor.substack.com/p/is-wuhan-a-red-herring?r=7in29&s=r